When a brand-name drug hits the market, its patent clock starts ticking. But for many top-selling medications, the real race doesn’t end when that first patent expires. Instead, companies begin building a fortress around the drug - not with walls, but with secondary patents. These aren’t about the active ingredient itself. They’re about the coating, the timing, the form, or even the way it’s used. And together, they can delay generic competition for years - sometimes more than a decade.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

A primary patent protects the actual chemical compound - the molecule that makes the drug work. Once that expires, generics can legally copy it. But secondary patents cover everything else: how the drug is made, how it’s delivered, what condition it treats, even its crystal structure. These are filed after the main patent, sometimes years later, and they’re not always about better medicine. Often, they’re about keeping prices high. Take Nexium, for example. AstraZeneca’s original drug, Prilosec, treated acid reflux. When its patent neared expiration, AstraZeneca launched Nexium - a version using just one half of the original molecule (the enantiomer). It wasn’t a breakthrough. Clinical studies showed it worked about the same. But because it was a new patentable form, Nexium got a fresh 8-year exclusivity window. Sales jumped to over $5 billion a year. Prilosec? Gone from shelves. This tactic is called “product hopping.”The 12 Types of Secondary Patents

Secondary patents come in many flavors. The United Nations lists 12 common categories used in pharma:- Formulation patents: Protect how the drug is packaged - extended-release pills, liquids, patches. These make up about 22% of all secondary patents.

- Polymorph patents: Cover different crystal shapes of the same molecule. GlaxoSmithKline used this to protect Paxil’s Form G, blocking generics for four years after the main patent expired.

- Method-of-use patents: Claim a new medical use. Thalidomide was originally a sedative. Decades later, it got patents for treating leprosy and multiple myeloma - extending its market life.

- Salts and esters: Minor chemical tweaks that don’t change how the drug works but let companies file new patents.

- Combination patents: Bundle two or more drugs into one pill. Often used to lock in patients who were already taking the individual drugs separately.

- Prodrugs and metabolites: Molecules that turn into the active drug inside the body. These are harder for generics to replicate without infringing.

These aren’t theoretical. In 2023, Drug Patent Watch found that a single drug like Humira had over 260 secondary patents. That’s not innovation - that’s a legal maze.

How Long Do They Really Extend Exclusivity?

Primary patents last 20 years from filing. But in pharma, the clock starts ticking long before the drug hits shelves. Clinical trials take 7-10 years. So by the time a drug is approved, you might have only 10-12 years of real market exclusivity left. Secondary patents plug that gap. A 2012 study in PLOS ONE found that for drugs with strong primary patents, secondary patents added 4-5 years on average. For drugs without strong compound protection, they added 9-11 years. That’s not a bonus - that’s a lifeline. And the impact isn’t just theoretical. A 2019 Health Affairs study showed drugs with secondary patents faced generic entry delays that were 2.3 years longer than those without. In some cases, it’s over a decade. AbbVie’s Humira, a top-selling drug, kept generics out until 2023 - even though its core patent expired in 2016. That’s 7 extra years of $20 billion in annual sales.

Why Do Companies Do This?

It’s simple math. The top 10 pharmaceutical companies hold 73% of all secondary patents. Why? Because the biggest sellers - drugs making over $1 billion a year - are the ones with the most patents. A 2012 study found that for every extra billion in annual sales, a company’s chance of filing a secondary patent went up by 17%. These aren’t random filings. Companies plan them 5-7 years before the primary patent expires. Teams of 15-20 patent lawyers work on a single drug. Each application costs $12-15 million. They’re not just protecting innovation - they’re protecting revenue. And it works. Generic manufacturers say navigating these patent thickets adds 3.2 years to their time-to-market and costs $15-20 million per product in legal fees. Many just give up.Where Do They Work - and Where Don’t They?

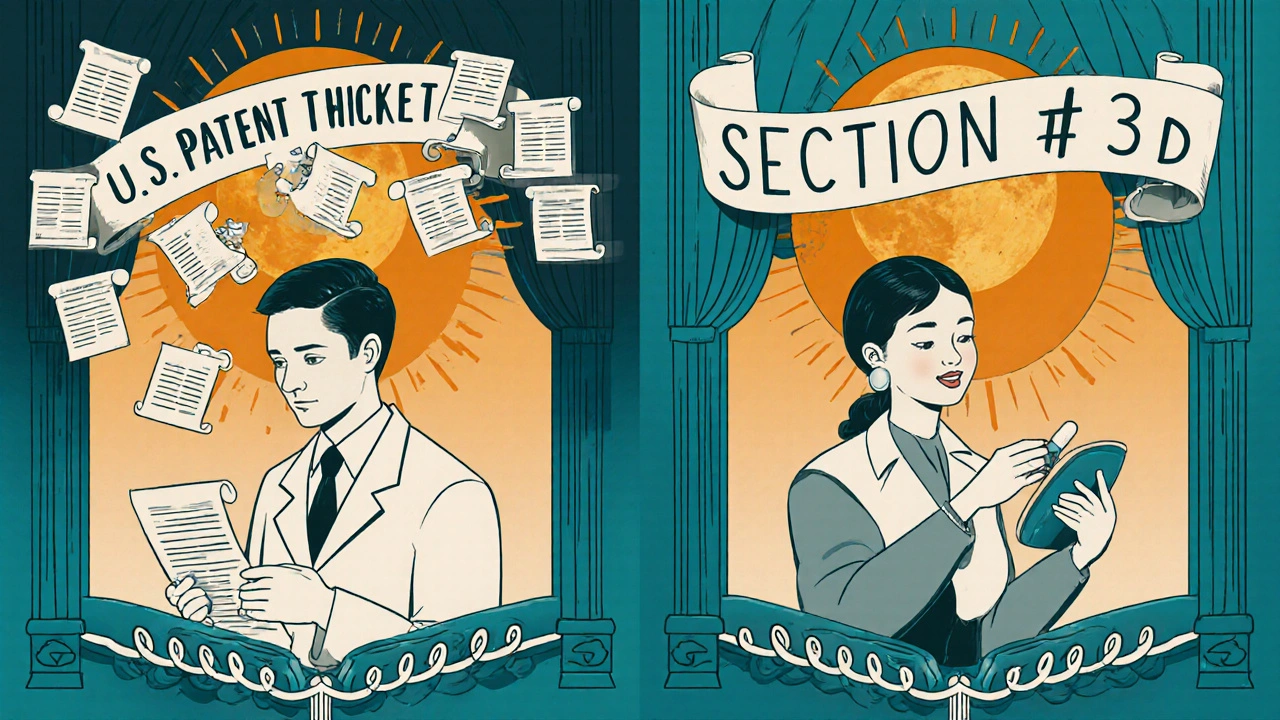

Not every country lets this happen. India’s patent law, Section 3(d), says you can’t patent a new form of an existing drug unless it shows “enhanced efficacy.” In 2013, Novartis tried to patent a new crystalline form of Gleevec. India rejected it. The court said it was just a “new form of a known substance” with no real improvement. That decision sent shockwaves through Big Pharma. Brazil requires health ministry approval before a patent can be enforced. The European Union demands “significant clinical benefit” for certain secondary patents. The U.S., under the Hatch-Waxman Act, has been the most permissive - allowing companies to list nearly any patent in the Orange Book, even if it’s not clinically meaningful. This creates a global patchwork. A drug might be protected in the U.S. for 15 more years, but face generics in India within months of its main patent expiring. Roche’s Tamiflu followed this pattern - blocked in the U.S. until 2016, but copied in India by 2011.

The Human Cost

Behind every delayed generic is a patient paying more. Pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts say secondary patents raise their annual costs by 8.3%. For patients on chronic meds - diabetes, heart disease, autoimmune disorders - that’s hundreds of dollars a month. Doctors report confusion. “Pharm reps push the new version right before generics come out,” says Dr. Emily Roberts, a primary care physician in California. “They tell patients it’s ‘better,’ but often it’s just more expensive.” Patient groups are split. Some, like Knowledge Ecology International, call secondary patents “evergreening” - a way to milk profits without real innovation. They point to Humira: $20 billion a year in sales, 264 patents, no meaningful improvement. But others point to cases where secondary patents helped. The American Cancer Society noted that new formulations of chemo drugs, protected by secondary patents, reduced side effects by 37% in trials. That’s real value.Is This System Changing?

Yes - slowly. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. gave Medicare new power to challenge secondary patents on high-cost drugs. The European Commission’s 2023 Pharmaceutical Strategy called patent thickets “a barrier to access.” The WHO labeled secondary patents as the top legal reason generic drugs are delayed in 68 low- and middle-income countries. Courts are getting stricter too. In 2023, a federal appeals court limited how broad antibody patents could be - a signal that not every tweak will be protected. But companies are adapting. Instead of filing dozens of weak patents, they’re focusing on fewer, stronger ones tied to actual clinical benefits. Dr. Roger Longman of Windhover Information predicts that by 2027, companies will need to prove their secondary patents deliver real patient improvements - or face rejection.What’s Next?

The era of the patent thicket isn’t over. But it’s changing. The pressure to lower drug prices, combined with smarter legal challenges and stricter patent standards, is forcing a reckoning. Companies that built empires on 200 patents for one drug are now looking at quality over quantity. For patients, the hope is that future secondary patents will be about better outcomes - not just longer profits. For generics, the fight is still on. For regulators, the challenge is clear: protect innovation without locking out access. The question isn’t whether secondary patents exist. It’s whether they’re serving medicine - or just the balance sheet.Are secondary patents legal?

Yes, secondary patents are legal in many countries, including the U.S. and Europe. But their validity depends on meeting patentability standards like novelty, non-obviousness, and utility. In places like India and Brazil, laws specifically restrict them unless they show significant therapeutic improvement. Courts in the U.S. are also tightening scrutiny, especially for patents that don’t add real clinical value.

How do secondary patents delay generic drugs?

Generic manufacturers must prove their product doesn’t infringe any listed patents before selling. If a brand-name company lists 50+ secondary patents in the FDA’s Orange Book, generics must either challenge each one in court or wait until all expire. Legal battles can take years. Even if a generic wins, the delay gives the brand time to shift patients to a newer, patented version - a tactic called product hopping.

Do secondary patents lead to better drugs?

Sometimes. Some secondary patents cover real improvements - like extended-release pills that reduce dosing frequency, or new formulations that cut side effects. But studies show only about 12% of secondary patents lead to meaningful clinical benefits. Most are minor changes - like switching from a tablet to a capsule - designed to reset the patent clock, not improve care.

What’s the difference between a primary and secondary patent?

A primary patent protects the active pharmaceutical ingredient - the core molecule. It’s filed early and lasts 20 years from filing. A secondary patent protects something about the drug - how it’s made, how it’s taken, or what it treats - and is filed later. Secondary patents don’t cover the molecule itself, but they can still block generics by creating legal barriers.

Can a drug have more than 100 patents?

Yes. Humira, a drug for autoimmune diseases, had over 260 secondary patents by 2023. Other top-selling drugs like Enbrel and Imbruvica have 100+ each. These aren’t all listed in official databases - some are kept as “reserve patents” to use in litigation if needed. The goal is to create a thick web of legal protection that makes it too costly or risky for generics to enter.

How do generic companies fight secondary patents?

Generic manufacturers file Paragraph IV certifications with the FDA, challenging the validity of listed patents. In 2022, 92% of secondary patents were challenged. But only 38% of those challenges succeeded in court. Many generics avoid the fight entirely due to cost - legal battles can run $15-20 million per drug. Some wait out the patents. Others partner with legal firms specializing in patent litigation.

They call it innovation, but it's just legal loophole gymnastics. I've seen the bills for my dad's autoimmune meds - $2k a month when the generic should've been $50. This isn't capitalism, it's extortion wrapped in a lab coat.

And don't get me started on product hopping. They don't improve the drug, they just repackage it like a new iPhone model no one asked for.

Oh, the tragic irony of modern pharmacology - where the pursuit of health has been sublimated into a Hegelian dialectic of capital, where the thesis of scientific progress is negated by the antithesis of corporate greed, only to be synthesized into a grotesque spectacle of patent thickets that strangle the very notion of accessible medicine.

We are not merely patients; we are commodities in a pharmaceutical theater, where the curtain rises on a stage of crystalline polymorphs and enantiomeric illusions, each one a Shakespearean soliloquy of profit disguised as science. The soul of healing has been auctioned to the highest bidder, and the auctioneer wears a white coat.

And yet - and yet - we cling to the myth that innovation still lives here, when in truth, the only thing evolving is the accountant’s spreadsheet. The patient? They are merely footnotes in the footnote of a footnote.

From a regulatory economics standpoint, the secondary patent ecosystem functions as a high-cost, low-yield signaling mechanism - essentially, a barrier-to-entry mechanism optimized for rent extraction rather than R&D efficiency.

The marginal utility of these patents is negligible beyond the 12% that demonstrate clinical improvement, yet the sunk cost of litigation and legal strategy is disproportionate. The Orange Book listing strategy is a textbook case of regulatory capture - the FDA’s system is being gamed by institutional actors with deep pockets and armies of IP attorneys.

What’s missing is a cost-benefit threshold. If a patent doesn’t improve bioavailability, reduce adverse events, or enhance compliance by >15%, it shouldn’t be eligible for listing. Simple. Rational. Evidence-based.

India said NO to this nonsense in 2013. Novartis came with their fancy crystals and fancy lawyers - and we told them: ‘Show us real benefit, not just a new shape.’

That’s why generics here are affordable. That’s why a diabetic in rural Bihar can get insulin for $2. That’s why your ‘life-saving’ drug costs 100x more in the U.S. and we don’t even blink.

Don’t call it innovation. Call it theft with a patent number.

Respectfully, I think we need to acknowledge that while some of this is abusive, there are cases where secondary patents actually help - like when a new formulation reduces side effects or makes dosing easier for elderly patients.

Maybe the solution isn’t to ban them entirely, but to create a clear, transparent standard for what counts as ‘meaningful improvement.’ Otherwise, we risk throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

You say ‘product hopping’ like it’s some kind of crime - but it’s not. It’s business. Companies invest billions to develop drugs, and if they can extend exclusivity through legally granted patents, then they’re exercising their rights under U.S. law.

And before you start crying about Humira, let’s not forget: without those patents, that drug might never have been developed in the first place. The incentive structure works - even if it’s ugly.

Also, ‘evergreening’ is a buzzword used by people who don’t understand patent law. Every patent must meet novelty and non-obviousness standards. If the courts are letting them through, then the system is working - just not the way you want it to.

Man, I’ve been on a few of these meds. The cost is insane. I get that companies need to make money, but when you’ve got a drug that’s been around for 15 years and they just change the pill color and call it ‘next-gen,’ it feels like they’re laughing at you.

My mom’s on one of those combo pills now - same active ingredients as two separate generics she used to take, but now it’s $400 a month instead of $60. And the rep told her it’s ‘more convenient.’

Convenient for who? Not me.

so like... if i take a drug and they just make it a capsule instead of a tablet and patent that... is that really a new invention? or just a packaging change?

also why do i have to pay for their lawyer bills just to get my medicine?

Honestly, I think the real win here is the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. It’s not perfect, but finally someone’s saying ‘enough.’

And the fact that courts are starting to crack down on antibody patents? That’s a sign the tide might be turning.

Let’s not forget - the goal isn’t to kill innovation. It’s to stop pretending that changing the pill’s coating is innovation. We can do better. We just need the will.