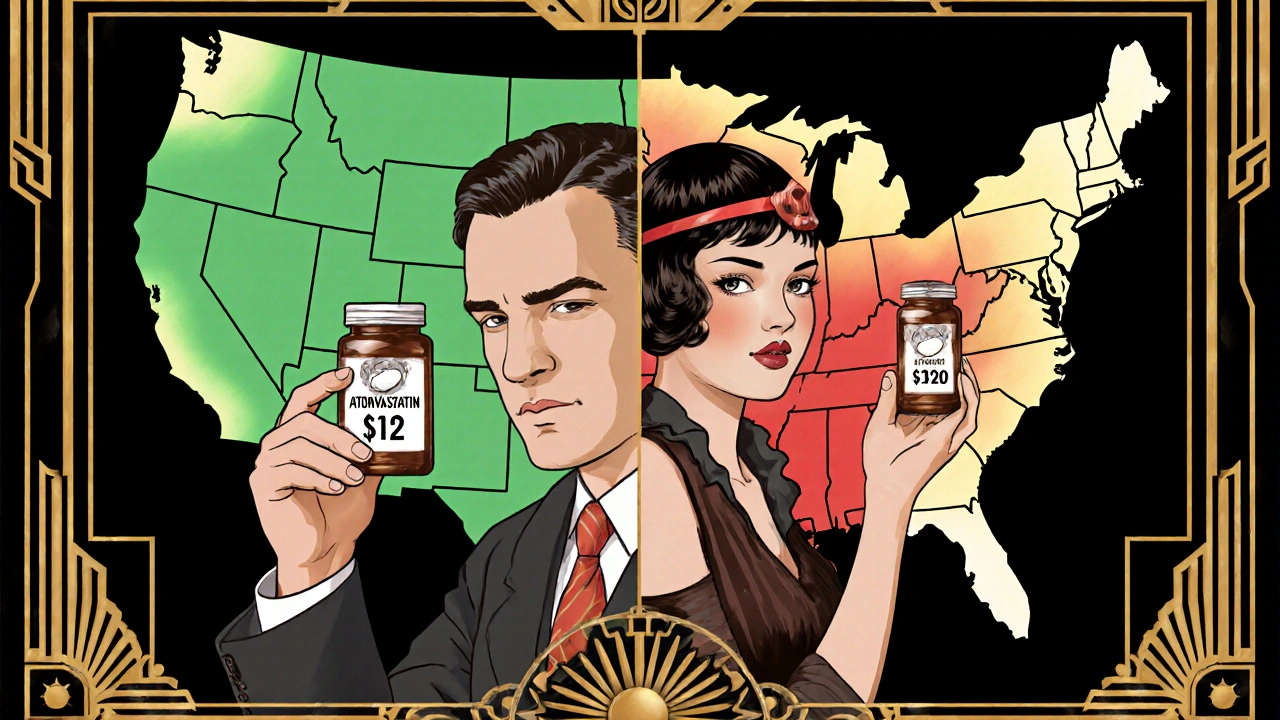

Ever bought a generic pill and been shocked by the price-only to find your neighbor paid half as much for the exact same medicine? It’s not a mistake. It’s not a scam. It’s just how the system works. In the U.S., the cost of a 30-day supply of generic atorvastatin can swing from $12 in Ohio to $120 in Texas, even if you have the same insurance. The same goes for metformin, levothyroxine, or amoxicillin. Why? Because generic drug prices aren’t set by a national standard. They’re shaped by a tangled web of state laws, middlemen, and market gaps that vary wildly from one border to the next.

How States Set the Rules (or Don’t)

There’s no federal price control on generic drugs. That means each state gets to play by its own rules-or, more often, no rules at all. Some states, like California and Vermont, passed laws requiring drug manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to report price hikes and justify cost increases. These transparency laws give patients and insurers a clearer view of what’s really going on. In states with strong transparency rules, patients pay 8-12% less on average for generics, according to Medicare claims data. But in states like Alabama or Mississippi, there’s little to no oversight. PBMs can negotiate secret deals with pharmacies, mark up prices without disclosure, and pass those inflated costs straight to you at the counter. And because these contracts are hidden, you have no way to know if you’re being overcharged-until you see the receipt. Maryland tried to stop price gouging on generics back in 2017. The law said pharmacies couldn’t charge more than a certain percentage above the wholesale cost. It made sense. It was fair. But a federal court shut it down, saying states can’t interfere with interstate commerce. That ruling sent a chilling message: even if your state wants to protect you, the system is designed to block it.Who’s Really in Charge? PBMs and Their Hidden Fees

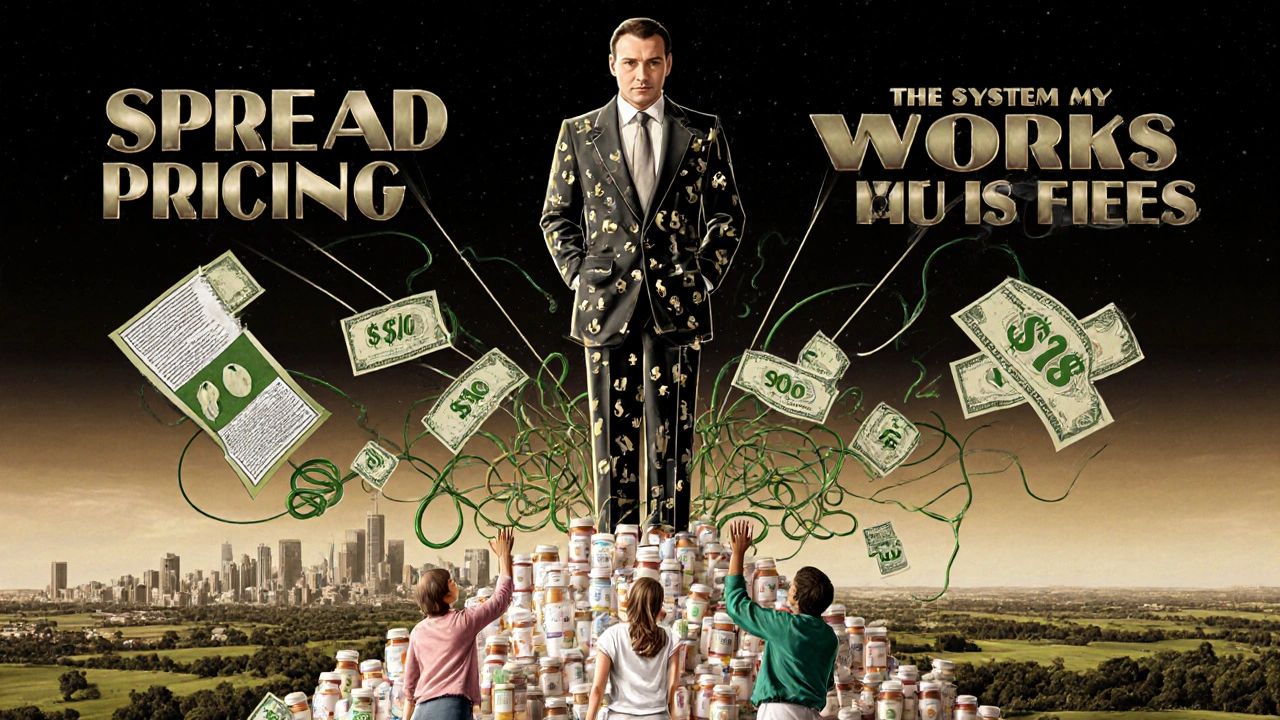

You might think your insurance company sets your drug price. But more often, it’s a Pharmacy Benefit Manager-PBM-that pulls the strings. These are giant middlemen hired by insurers and employers to manage drug benefits. They negotiate discounts with drugmakers and pharmacies. But here’s the catch: they don’t always pass those savings on to you. PBMs often use a system called “spread pricing.” They tell your insurer they paid $5 for a bottle of generic lisinopril. They charge your insurance $15. Then they tell the pharmacy they’ll pay $8. The pharmacy gets $8. Your insurer pays $15. You pay your $10 copay. The PBM pockets $7. And you never know. That $7 could be $20, depending on your state’s regulations-or lack of them. A 2022 study from the USC Schaeffer Center found U.S. consumers overpay for generics by 13% to 20% because of these hidden practices. And it’s worse in states where PBMs have little competition. In places with only one or two big PBMs running the show, they can set prices however they want. No one’s watching.Why Cash Often Beats Insurance

Here’s the paradox: if you’re paying for a generic drug, your insurance might be making it more expensive. Most insurance plans have a deductible or copay structure that doesn’t reflect the real cost of the drug. A 90-day supply of generic atorvastatin might cost your insurer $10, but your copay is $45 because your plan’s formulary lists it as a “tier 2” drug. Meanwhile, if you pay cash at a pharmacy like Costco, Walmart, or a service like GoodRx, you might pay $10. In fact, 97% of cash payments for prescriptions in the U.S. are for generic drugs. Why? Because cash bypasses the entire PBM system. You’re paying the pharmacy’s actual cost-not what the insurer agreed to pay after markup. GoodRx data from 2022 showed price differences of up to 300% between neighboring states for the same drug. One pharmacy in rural Georgia charged $78 for metformin. Just across the line in Florida, the same pill cost $18. That’s not inflation. That’s a broken system.

Market Competition (Or Lack Thereof)

The more pharmacies in an area, the lower the price. That’s basic economics. But in rural states or small towns, there might be only one pharmacy. That pharmacy doesn’t have to compete. So it charges more. In cities like Chicago or Seattle, you’ve got CVS, Walgreens, Target, Walmart, and independent pharmacies all fighting for your business. Prices stay low. In places like West Virginia or North Dakota, you might have to drive 50 miles to find another option. And if the only pharmacy in town is owned by a PBM-affiliated chain, they can charge whatever they want. The FDA approved over 800 generic drugs in 2017-the most ever. That should have driven prices down. And it did… but only in markets where competition was already strong. In areas with fewer pharmacies or less transparency, those savings never reached patients.Medicaid and Reimbursement: A State-by-State Patchwork

Medicaid, which covers 80 million Americans, pays for most generic drugs in low-income communities. But how much it pays varies by state. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which updates monthly and reflects what pharmacies actually pay. Others use outdated benchmarks or formulas that don’t match reality. In states that use NADAC, pharmacies get paid fairly. In states that don’t, pharmacies lose money on generics. So they make it up on you. They raise copays. They push you toward brand-name drugs. Or they just don’t stock certain generics at all. A 2023 update from CMS changed how Medicaid calculates rebates. That change created new gaps. In some states, reimbursement rates dropped. In others, they stayed the same. The result? A patchwork of access and affordability that depends entirely on where you live.

What You Can Do Right Now

You can’t change state laws. But you can change how you pay.- Always check GoodRx or SingleCare before you pay. Enter your drug, dose, and zip code. See what cash price is available.

- If the cash price is lower than your copay, pay cash. Tell the pharmacy you’re paying out of pocket. They’ll process it that way.

- Use Walmart’s $4 list or Costco’s pharmacy prices. Many generics cost under $10 there-even with no insurance.

- If you’re on Medicare, remember the $35 cap on insulin and the $2,000 out-of-pocket limit starting in 2025. That helps, but only if you’re enrolled.

- Ask your pharmacist: “What’s the lowest price I can pay today?” They often have unadvertised discounts.

So let me get this straight: we have a $120 pill in Texas, a $12 pill in Ohio, and no one’s held accountable? Of course not. Because capitalism isn’t broken-it’s *perfectly* designed to exploit the desperate. You think this is about health? No. It’s about extracting every last dime from people who can’t afford to ask why. The system isn’t broken-it’s working exactly as intended. And you? You’re the fuel.

This isn’t healthcare-it’s a carnival sideshow with price tags. One pharmacy charges $78 for metformin? That’s not a pricing error, that’s a middle finger to the working class. And don’t get me started on PBMs-they’re the vampire squid of pharma, tentacles wrapped around every damn prescription. I’m not mad, I’m just… emotionally devastated. And also, I just paid $8 cash for my lisinopril. Fuck them all.

The problem is not PBMs. The problem is not states. The problem is that we have allowed weak, soft, overregulated, politically correct nonsense to replace common sense. We have a free market for everything else-cars, phones, TVs-but when it comes to medicine, we demand socialism and then complain when it doesn’t work. The solution? Let the market work. Remove state interference. End Medicaid price controls. Let pharmacies compete. Prices will fall. The left wants control. The right wants profit. Neither wants the patient to win.

Bro, i just used goodrx and got my metformin for $5 at walmart. same drug, same dose, same pharmacy chain. i live in rural india and even here its cheaper than texas. how is this possible? the system is rigged. but you can still beat it. cash is king. always check prices. dont trust insurance. they dont care.

This is all part of the Great Pharma-Elitist Control Matrix 🤫💉. PBMs are just frontmen for the Illuminati’s pharmaceutical cabal. They’ve been manipulating NADAC data since 2014 using quantum algorithms fed by CDC surveillance drones. That’s why your cash price is lower-it bypasses the AI-driven price-optimization matrix. Also, if you’re not using a crypto pharmacy wallet, you’re being exploited. The FDA? Complicit. Medicare? A puppet. The $35 insulin cap? A distraction. Wake up. 🔮💊

Let’s be real. PBMs aren’t middlemen-they’re *predators*. They’re the reason your grandma’s thyroid med costs more than her monthly Netflix subscription. And the worst part? They don’t even *make* anything. They just sit in a Chicago office, shuffle numbers, and laugh while you cry at the register. It’s not capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy receipt.

I work as a pharmacist in rural Maine, and I see this every single day. People come in with tears in their eyes because they can’t afford their meds. I’ve had patients skip doses, split pills, or just not fill them at all. But here’s the thing-you’re not powerless. I’ve helped dozens of people pay cash instead of using insurance. One lady saved $87/month on her atorvastatin just by asking. It’s not perfect, but it’s something. And if you’re reading this? Go to GoodRx right now. It takes 90 seconds. You can change your life with one click. You’re not alone. 💙

Cash beats insurance every time. Stop overthinking it. Just go to Walmart. Or Costco. Or use GoodRx. If the cash price is lower than your copay-pay cash. It’s that simple. No drama. No politics. Just a better deal. You deserve to be healthy. Don’t let bureaucracy steal your medicine. Do the thing. Now.

You think this is bad? Wait till you find out the same company that makes your generic atorvastatin also owns the PBM that sets your price. And the pharmacy that sells it? Owned by the same parent company. And the insurance? Same. It’s all one giant incestuous oligopoly. They’re not just profiting-they’re colluding. And the FDA? They’re on payroll. Wake up. This isn’t a glitch. It’s a feature.

I’ve always wondered why we treat medicine like a commodity. It’s not. It’s a human right. But we’ve turned it into a speculative asset class. People die because they can’t afford the pill. And we’re supposed to be okay with that? We call this freedom? This isn’t capitalism. This is moral decay dressed in a lab coat. The real tragedy isn’t the price difference-it’s that we’ve stopped being outraged.

I used to think this was just about money. But now I think it’s about dignity. The fact that someone in Ohio can get the same pill for a tenth of the price means we’ve built a system that rewards geography over humanity. It’s not just unfair-it’s dehumanizing. And yet we keep clicking ‘pay’ without asking why. We’ve normalized exploitation. That’s the real crisis. Not the price. The silence.

The structural asymmetry in pharmaceutical reimbursement mechanisms across jurisdictions reveals a profound regulatory fragmentation. While market-based pricing may theoretically encourage competition, the absence of transparent pricing benchmarks and the dominance of non-transparent PBM intermediaries fundamentally distort consumer outcomes. A harmonized, data-driven, state-federal coordination framework-anchored in NADAC and enforced via audit protocols-would mitigate these disparities. The current patchwork is not merely inefficient; it is ethically indefensible.