QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Enter your information above and click "Calculate Risk" to see the risk assessment.

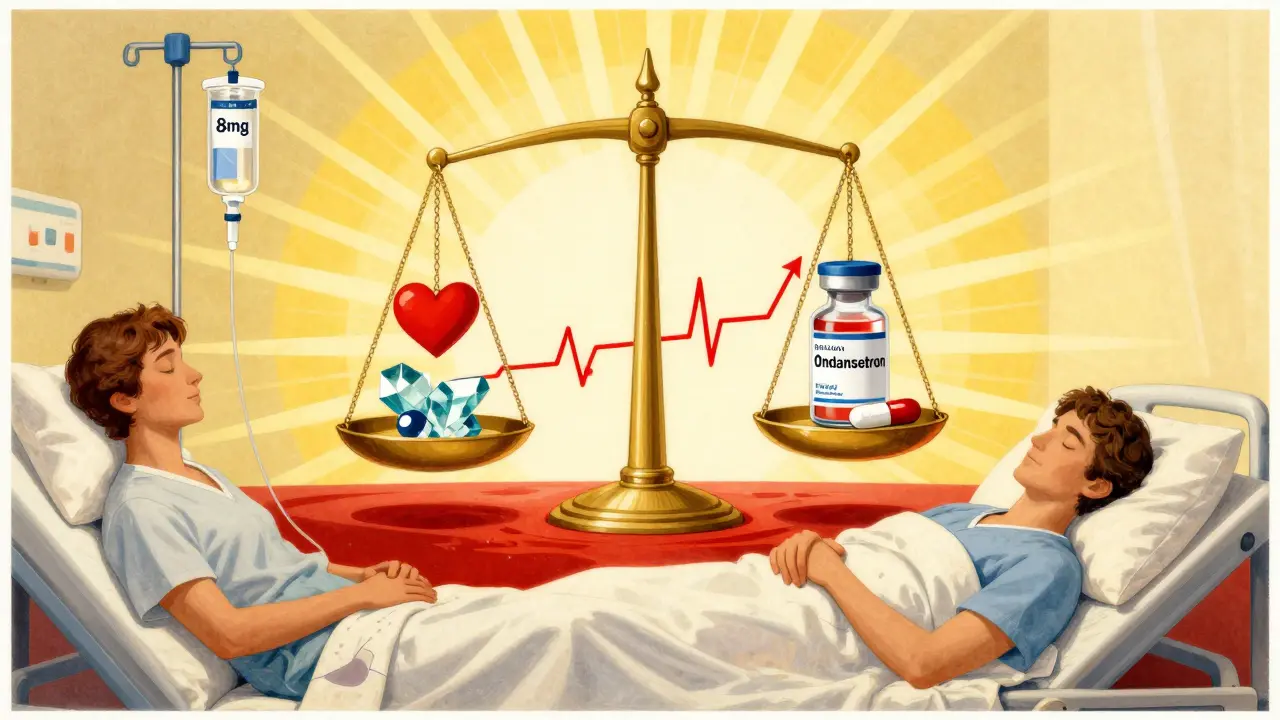

When you're feeling sick to your stomach after chemotherapy or surgery, ondansetron can feel like a lifesaver. It works fast, it’s widely available, and for years, doctors reached for it without a second thought. But here’s the part no one talks about until something goes wrong: ondansetron can mess with your heart’s rhythm - and sometimes, that’s deadly.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

Your heart doesn’t just beat - it electrically recharges between beats. That recharge time is measured as the QT interval on an ECG. If it gets too long, your heart can slip into a dangerous rhythm called torsades de pointes. It’s rare, but when it happens, it can cause sudden cardiac arrest. And yes, common anti-nausea drugs like ondansetron can trigger this.

This isn’t theoretical. Between 2012 and 2022, the FDA recorded 142 cases of torsades linked to ondansetron. Most involved IV doses over 16 mg. Patients didn’t need to be elderly or frail - just someone with even a small heart condition, low potassium, or on another QT-prolonging drug. That’s when the risk spikes.

Why Ondansetron Affects Your Heart

Ondansetron blocks a specific potassium channel in heart cells called hERG. This channel helps the heart reset after each beat. When it’s blocked, the heart takes longer to recharge - and that’s what stretches the QT interval. The effect isn’t subtle. A 2011 study showed IV ondansetron lengthens QTc by an average of 20 milliseconds within minutes. That’s a big jump. For context, a 10-millisecond increase raises arrhythmia risk by 5-7%.

The FDA looked at this closely in 2012. They found:

- At 8 mg IV: QTc increased by 6 ms

- At 32 mg IV: QTc increased by 20 ms

That’s why the FDA banned single 32 mg IV doses. They said: no more than 16 mg at once. Even then, many hospitals now cap it at 8 mg for patients with any heart risk.

Not All Antiemetics Are Created Equal

Not every anti-nausea drug carries the same risk. Here’s how they stack up:

| Drug | Class | Max QTc Increase (ms) | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 20 | High (IV) |

| Dolasetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 25+ | Very High |

| Granisetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 5-10 | Low |

| Palonosetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 9.2 | Low |

| Droperidol | Butyrophenone | 15-20 | High |

| Prochlorperazine | Phenothiazine | 10-15 | Moderate |

Granisetron and palonosetron are safer bets if you’re at risk. The American Society of Clinical Oncology now recommends palonosetron over ondansetron for patients with heart problems. Why? Because it does the same job - stopping nausea - without the same cardiac punch.

Who’s at Real Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. Risk skyrockets if you have:

- Pre-existing long QT syndrome

- Heart failure

- Low potassium or magnesium

- Slowed heart rate (bradycardia)

- Already taking other QT-prolonging drugs (like certain antibiotics, antidepressants, or antifungals)

- Age over 75

A Johns Hopkins case series in 2019 found three out of 15 elderly patients developed QTc over 500 ms after a standard 8 mg IV dose. That’s not a fluke. That’s a pattern.

Even healthy people aren’t immune. A 2020 survey of anesthesiologists found that 63% had switched to lower doses - not because they saw a crisis, but because they saw enough small changes in ECGs to worry.

What Hospitals Are Doing Now

Since the FDA warning in 2012, hospitals have had to change. Here’s what’s actually happening on the ground:

- 92% of U.S. hospitals now have formal protocols for ondansetron use (up from 37% in 2011).

- Many require a baseline ECG before giving IV ondansetron if the patient has any heart risk factors.

- Some mandate correction of low potassium or magnesium before administration.

- Pharmacists often verify QTc calculations before high-dose doses are given.

- ECG monitoring for 4 hours after IV ondansetron is now standard in ERs and oncology units for high-risk patients.

One ER doctor from Massachusetts General told a hospital forum: “We switched to dexamethasone alone for low-risk nausea. No ECG needed. No risk. And it works.”

What You Can Do - Patient and Provider

If you’re a patient:

- Ask: “Is this the safest option for my heart?”

- Know your history: Have you ever had a prolonged QT? Low potassium? Heart issues?

- Ask if an oral dose is an option - it’s much safer than IV.

If you’re a provider:

- Never give 32 mg IV. Ever.

- Cap IV doses at 8 mg for patients over 65, with heart disease, or on other QT drugs.

- Check electrolytes before giving IV ondansetron - especially potassium and magnesium.

- Consider alternatives: granisetron, palonosetron, dexamethasone, or aprepitant.

- Monitor ECG for at least 2-4 hours after IV administration in high-risk patients.

And don’t assume “standard dose” is safe. What was normal in 2010 isn’t safe in 2025.

The Bigger Picture

Ondansetron still works. It’s effective. In fact, it has a 71% success rate in stopping acute chemo nausea - better than granisetron’s 63%. That’s why it’s still used. But effectiveness doesn’t override safety.

The market is shifting. IV ondansetron use has dropped 22% since 2012. Sales of safer alternatives like palonosetron and aprepitant have grown by over 15% annually. The future isn’t about bigger doses - it’s about smarter choices.

Research is moving toward personalized dosing. A 2022 study found patients with a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer gene variant are more likely to have exaggerated QT prolongation. That means someday, your genes might tell your doctor how much ondansetron you can safely take.

For now, the rule is simple: if your heart is even a little fragile, don’t gamble with a drug that can stop it.

Can I still take ondansetron if I have a heart condition?

If you have a history of long QT syndrome, heart failure, or bradycardia, avoid IV ondansetron entirely. Oral ondansetron is safer, but even then, your doctor should check your ECG and electrolytes first. Safer alternatives like granisetron or dexamethasone are often preferred.

Is oral ondansetron safe for the heart?

Yes, oral ondansetron carries much less risk than IV. The FDA says single oral doses up to 24 mg are safe for most people, even with heart conditions. The slow absorption avoids the sharp spike in blood levels that causes QT prolongation. Still, if you’re high-risk, talk to your doctor before taking any form.

What’s the maximum safe IV dose of ondansetron?

The FDA recommends no more than 16 mg as a single IV dose. Many hospitals now limit it to 8 mg for patients over 65, with heart disease, or on other QT-prolonging drugs. Never exceed 16 mg in one dose - and never give 32 mg.

Can ondansetron cause sudden death?

Yes - but only in rare cases, usually when high IV doses are given to people with existing risk factors. Between 2012 and 2022, 142 cases of torsades de pointes were linked to ondansetron. Most involved doses over 16 mg IV in patients with heart problems or low electrolytes. The risk is small, but the outcome can be fatal.

Are there better alternatives to ondansetron?

Absolutely. Palonosetron causes less QT prolongation and is now preferred in patients with cardiac risk. Granisetron (especially transdermal) is also safer. Dexamethasone is a non-cardiac option often used alone or combined. Aprepitant is another alternative, especially for delayed nausea. Ask your doctor if one of these is right for you.

Final Thought

Medicine isn’t about using the strongest drug - it’s about using the right one for the right person. Ondansetron saved lives, but it also cost some. The lesson isn’t to avoid it entirely. It’s to respect its power. Check the ECG. Check the potassium. Choose the dose like your life depends on it - because sometimes, it does.

OMG I had no idea ondansetron could do this 😱 My grandma got it after chemo and then her heart went haywire-turns out she had low potassium and no one checked. We were lucky she didn’t crash. Please, everyone, ask for an ECG before IV doses. Seriously. 💔

Let’s be clear-this isn’t ‘risk,’ it’s institutional negligence masked as ‘standard care.’ The FDA’s 2012 warning was a tepid slap on the wrist. They knew. Hospitals knew. Yet we still see 32mg IV doses being administered like it’s coffee. This is pharmacovigilance theater. The real crime is how long it took for anyone to care until someone died.

just read this and my heart sank 😔 i work in oncology and we switched to palonosetron last year after a patient had torsades. i didnt even know ondansetron could do that. thanks for the breakdown. i’ll make sure we’re checking k+ before every dose now. ty for sharing this.

As a registered nurse with 18 years in critical care I must emphasize that adherence to updated protocols is not optional. The data is unequivocal. Failure to screen for QT risk factors constitutes a breach of the standard of care. Institutions that ignore this are not just negligent-they are endangering lives under the guise of convenience.

Big thanks for laying this out so clearly 🙏 I used to think ondansetron was the gold standard until I saw a guy go into VT after a 16mg IV. Now I always ask: ‘Any heart issues? Electrolytes checked?’ If not, I grab granisetron. It’s cheaper, safer, and works just as well. No drama, no ECGs, no stress. Win-win.

Oh wow, so now we’re blaming the drug because doctors are too lazy to check potassium? Let me guess-you also think aspirin causes bleeding because people don’t read the label. Wake up. People die from everything. You don’t stop using life-saving meds because someone was dumb. That’s not medicine, that’s fearmongering.

One must interrogate the epistemological foundations of clinical pragmatism. The hegemony of pharmacological efficacy as the primary metric of therapeutic success obscures the ontological vulnerability of the corporeal substrate. Ondansetron, as a pharmacological signifier, functions within a biopolitical regime that prioritizes speed over somatic integrity. The QT interval, then, becomes a site of biostatistical subjugation.

As an American citizen and former ICU nurse, I find it unacceptable that our healthcare system still allows this. We have the data. We have the guidelines. Yet hospitals continue to cut corners. This isn’t just medical negligence-it’s a betrayal of public trust. We must demand accountability. Not just from doctors, but from hospital administrators who prioritize profits over patient safety.

It is fascinating how we treat drugs as neutral tools, yet they are embedded in power structures-pharmaceutical marketing, hospital protocols, physician habits. Ondansetron’s rise was not purely clinical; it was commercial. The decline now is not due to moral awakening, but because the cost of lawsuits and bad press outweighs the convenience. We are not evolving-we are reacting to consequences.

Bro, palonosetron is the real MVP here-like the chill older sibling who shows up late but fixes everything without drama. Granisetron’s the quiet nerd who actually knows what’s up. Ondansetron? That guy who shows up with a 32mg IV like he’s trying to win a drug-off. We gotta retire him before he breaks someone’s heart. 🫡

For anyone new to this-don’t panic. Ondansetron isn’t evil. It’s just powerful. Think of it like a chainsaw: amazing for cutting trees, deadly if you don’t wear gloves. Check potassium. Check ECG. Use lower doses. Swap to safer options when needed. Small steps save lives. You don’t need to be a genius-just careful.

Let me tell you about the time I saw a 78-year-old woman with CHF, on amiodarone, with a potassium of 3.1, get 16mg IV ondansetron because the resident was ‘in a rush.’ She coded 22 minutes later. The family cried. The hospital blamed ‘unforeseen complications.’ I’ve been in this game 27 years. This isn’t a ‘risk.’ It’s a predictable, preventable, and utterly avoidable tragedy-and it happens every damn week. And no one gets fired. No one gets punished. Just another footnote in a chart.

Wow so now we’re supposed to be terrified of nausea meds? Next you’ll tell me water can cause hyponatremia. Maybe if people didn’t eat like garbage and let their potassium drop to 2.8, this wouldn’t be an issue. Blame the patient. Blame the doctor. Blame the drug. But don’t blame the fact that nobody checks their electrolytes before popping pills like candy.

They’re all just trying to scare you into buying expensive alternatives. Palonosetron costs 10x more. Dexamethasone? It causes insomnia, mood swings, and blood sugar spikes. Ondansetron is still the most effective. If your heart can’t handle it, maybe you shouldn’t be getting chemo. Stop weaponizing fear to push profit-driven guidelines.