Just because a brand-name drug’s patent expires doesn’t mean the generic version shows up the next day. In fact, it often takes years-sometimes more than two-for patients to get access to cheaper versions of medicines they’ve been paying top dollar for. This isn’t a glitch. It’s the system. And understanding how it works could save you hundreds-or even thousands-of dollars a year.

Patent Expiration Isn’t the Starting Line

Most people think: patent expires → generics arrive. Simple. But the reality is messier. A pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But here’s the catch: drug development takes 8 to 10 years before the drug even hits shelves. That means by the time a brand-name drug like Lipitor or Crestor hits the market, it’s already halfway through its patent life. So the real window for exclusive sales? More like 7 to 12 years, not 20. And even then, patents aren’t the only barrier. The FDA gives extra protection called "exclusivity"-separate from patents-that can add years. A new chemical entity gets 5 years of exclusivity. If a company tests the drug for new uses in kids, they get an extra 6 months. Orphan drugs (for rare diseases) get 7 years. These aren’t loopholes-they’re legal tools built into the system to encourage research. But they also delay generic competition.The ANDA Process: Fast, But Not That Fast

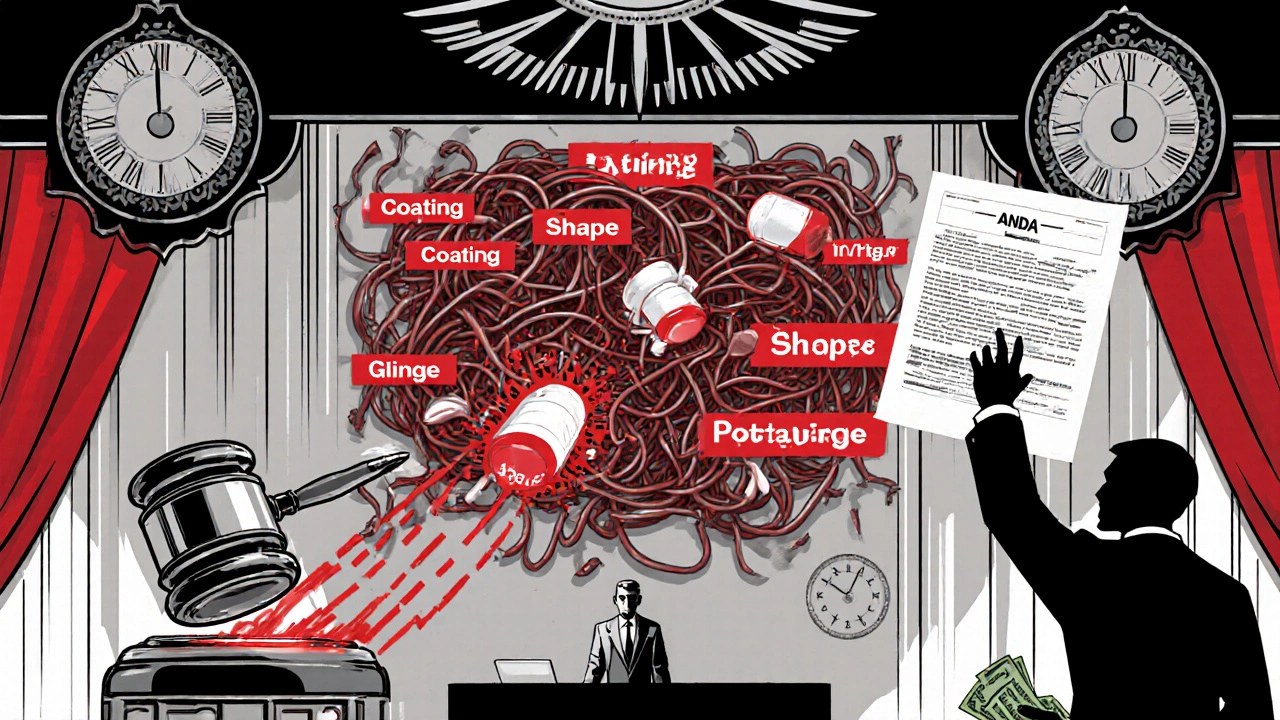

Generic manufacturers don’t have to redo clinical trials. Instead, they file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). All they need to prove is that their version works the same way in the body as the brand-name drug-same active ingredient, same dose, same effect. Sounds easy, right? It’s not. The FDA’s average review time for an ANDA is over 25 months. And that’s just the start. Before filing, generic companies spend 18 to 24 months (or longer for complex drugs) developing the formulation, testing stability, and setting up manufacturing lines that meet FDA standards. For pills with tricky coatings or injectables with sterile processes, it can take three years just to get ready to apply. And here’s where things get complicated: patents don’t just cover the active ingredient. There are also patents on how it’s made, how it’s packaged, even how it’s used. A single drug can have 10, 14, or even 20 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. That’s called a "patent thicket." Each one must be addressed before a generic can legally launch.Paragraph IV Certifications and the 30-Month Stay

When a generic company files an ANDA, they must say whether they believe the brand’s patents are invalid or won’t be infringed. This is called a Paragraph IV certification. It’s a legal challenge. And if the brand-name company sues within 45 days, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months-unless the court rules sooner. That 30-month clock sounds like the main delay. But studies show it’s rarely the real bottleneck. On average, generic drugs launch 3.2 years after the 30-month stay ends. Why? Because most delays happen before the lawsuit even starts. Companies are busy developing products, waiting for patent challenges to resolve, or negotiating settlements.

180-Day Exclusivity: The First-Mover Advantage

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generics can enter during that time. Sounds like a big win? It is-but it’s also a trap. That 180-day window forces the first filer to launch fast. If they can’t get their manufacturing right, if there’s a quality issue, or if they’re still in litigation, they lose the exclusivity. About 22% of first filers forfeit it because they’re not ready. And if they don’t launch within 75 days of FDA approval, they lose it anyway. So even when the patent is cleared, the race to market is a high-stakes game of speed and precision.Why Some Drugs Take Forever

Not all drugs are created equal. Small molecule pills-like those for high blood pressure or cholesterol-usually see generics within 1.5 years of patent expiration. But complex drugs? Not so fast. Biologics-injectable drugs made from living cells, like Humira or Enbrel-face a whole different system. The BPCIA, passed in 2010, created a slower approval path for biosimilars (the generic version of biologics). These take an average of 4.7 years to enter the market after the brand’s exclusivity ends. Even within small molecules, delays vary. Cardiovascular drugs face delays of 3.4 years on average. Dermatology drugs? Just 1.2 years. Why? Because some companies pile on patents for minor changes-new coatings, different pill shapes, new dosing schedules. These aren’t meaningful improvements. They’re legal tactics called "evergreening." A 2024 Brookings study found 68% of brand-name drugs get a new patent within 18 months of the original expiring.Settlements That Delay, Not Speed Up

Here’s one of the most controversial parts: patent lawsuits often end in settlements. And sometimes, those settlements include payments from the brand-name company to the generic maker to delay launch. These are called "reverse payments." The FTC estimates these deals cost consumers $3.5 billion a year. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled such secret deals can violate antitrust laws. Since then, the number has dropped-but they haven’t disappeared. A 2022 Congressional Research Service report found that settlements still delay generic entry by an average of 2.1 years. Meanwhile, the FDA approved 1,165 generic drugs in 2021. But only 62% actually reached the market within six months of approval. Why? Because even after the FDA says "yes," manufacturers might still be stuck in litigation, waiting for supply chain issues to resolve, or dealing with last-minute patent claims.

Patent expiration doesn’t mean instant access because the system is rigged to protect profits, not patients. The 180-day exclusivity window sounds fair until you realize it’s a trap that lets one company milk the market while others scramble. And if they mess up manufacturing? Everyone loses. We need structural reform, not Band-Aids.

Let’s be real - this isn’t about innovation, it’s about corporate greed disguised as legal strategy. Evergreening? Patent thickets? Reverse payments? These aren’t loopholes - they’re crimes. The FDA’s just a rubber stamp for Big Pharma, and we’re the ones paying the price in co-pays and skipped doses. Wake up, people.

ANDA review latency exceeds 25 months due to regulatory inertia and resource misallocation. Bioequivalence protocols remain antiquated. The GDUFA targets are aspirational, not operational. Supply chain fragility exacerbates delays. Structural reform is non-negotiable.

Okay so here’s the real tea - the government’s in bed with Big Pharma, right? You think the 30-month stay is about protecting IP? Nah. It’s a bribe disguised as law. And those reverse payments? That’s not negotiation, that’s bribery with a law degree. I’ve seen docs where companies pay generics to NOT launch - for YEARS. And you think the FDA doesn’t know? They’re complicit. The whole system’s a Ponzi scheme built on sick people’s desperation. And now they’re using AI to speed up the scam? Brilliant. Just brilliant.

OMG YES. I’ve been on statins for 5 years, and my generic didn’t show up for 22 months after patent expiry. I was paying $400/month until I found a discount card. The system is literally designed to make you suffer. And the worst part? Your pharmacist knows the generic is approved - they just can’t dispense it yet. It’s like having a key to a locked room and being told to wait for the landlord’s approval. #PharmaScam

It’s not enough to expose the mechanics - we must demand accountability. The concentration of market power among Teva, Viatris, and Sandoz is anticompetitive by design. The CREATES Act and Orange Book reforms are steps, but they’re reactive. We need mandatory disclosure of all patent filings, public funding for generic development, and criminal penalties for reverse payments. Patient access is a human right, not a corporate perk.

USA rules. Other countries get cheap meds because they dont protect innovation. If you want cheap drugs, stop suing companies for making them. We build the drugs, they copy. Simple. Stop crying about patents. America made this possible. Now you wanna take it away? No thanks. I’ll pay more so our scientists keep inventing.

Anyone else notice that the drugs with the longest delays are the ones that treat chronic conditions? Diabetes, hypertension, cholesterol - stuff people take for life. That’s not coincidence. That’s targeting. They know you’ll keep paying. And the FDA approves generics but they sit in warehouses because the brand company still owns the distribution channels. It’s not a delay - it’s a lockout.

It’s ironic. We celebrate the free market, but when it comes to life-saving medicine, the market is anything but free. We’ve turned healthcare into a legal chess game where the pieces are patients and the board is written by lawyers. The real innovation isn’t in the drug - it’s in the loopholes.

The data presented here is both comprehensive and alarming. The median delay of 18 months between patent expiration and generic availability represents a systemic failure of public policy. The aggregation of regulatory, legal, and economic barriers constitutes a de facto market monopoly extension. It is imperative that legislative reform prioritize patient access over corporate profit maximization. The current framework is neither ethical nor economically sustainable.

Typical American whining. In India we get generics in 3 months. Why? Because we don’t let corporations own the law. You think patents are sacred? They’re just tools for rich guys to keep poor people sick. Your system is broken because you worship money more than medicine. Stop blaming the FDA. Blame the CEOs who fund your politicians.